From the earliest days of ocean travel, the Passenger List has been the social, style and aesthetic mirror of the day. For the ephemera collector-cum social historian, they provide a fascinating study. They occupy one corner of my ocean liner collection, and provide an ongoing source of interest in terms of not only the contents but also the covers.

Early lists showed the name of each passenger, title, if any, and city or town of residence. By the time of the first meal, the experienced traveller would have reviewed the Passenger List to see whether there were any ‘important’ people on board. If one were in First Class (a.k.a. Saloon, First Saloon, or First Cabin), the quest of the voyage would be to meet celebrities in person and perhaps ask for their autograph. Members of the aristocracy, barons of business, senior clergy, and parliamentarians were all of interest. Beyond that, one would look for other passengers (in the same class) from the traveller’s home community if it were shown on the list.

Equally important for the passenger was remembering the names of the other parties seated at their dinner table. Many passenger lists are annotated with tick marks, underlining, or other symbols as an aide memoire for the names of table-mates. Even more important for some of the elite was the entourage accompanying other travellers in their class. For example, in an R.M.S. Aquitania 1920 passenger list one sees “The Right Hon. The Earl of Craven and Valet” and “The Countess of Craven and Maid”. Numerous other passengers were accompanied by maids or valets. However, some passengers took the competition to a higher level, and the same passenger list shows “Mrs. Leatherbee and three maids.” The likely reaction by the other super-rich would be to bring more of the household staff on the next trip, so that they could trump the entourage of their fellow travellers in the social set. In total there were 20 maids and 6 valets on that voyage. The list also contains “Mr. C. P. Coleman and Secretary”, Master John Raiss and Tutor”, and Master Gallagher and Nurse.” Other lists show chauffeurs, suggesting that the owners’ also brought their own motor vehicles on the ship.

Note that servants didn’t have names. They were merely an anonymous appendage to the names of their masters. This underscores the almost serf-like conditions for staff in many upper class households. Further, servants had small quarters although in close proximity to their masters. Deck plans of the RMS Mauretania of the same era show small quarters on the deck below the First Class suites, with nearby stairways. It wasn’t just maids and servants that were the equivalent of nameless chattels. A pocket-sized 1879 passenger list of Anchor Line’s Devonia shows “Capt. Charles Porter and wife.”

The apex of social competitiveness may well have occurred during a three-day cruise on the RMS Berengaria to observe the Royal Naval Review at Spithead in 1935, to commemorate the King’s 25th Anniversary on the throne. The passenger list shows icons such as Rudyard Kipling and Mrs. Kipling (“and Maid”); Mr. Frederick M. Elgar; Lady Brocklebank; Mrs. Oswald Mosley; the Hon. Mary, Jean, and Sheila Parnell; five members of Canada’s Eaton family, owners of Canada’s largest department store chain; and a phalanx of the nobility and Members of Parliament. If one were to combine this passenger list with those of the R.M.S. Lancastria and the R.M.S. Majestic, the other two passenger ships providing cruises to view the Review, a significant portion of the British upper class of the day would be represented.

It would be interesting research to track the number of maids, valets and other servants on passenger lists of a ship over many years, to trace the reduction in the number of servants and other household staff. The best ships to use would probably be one or both of the R.M.S. Aquitania, a large, prestigious four-stacker in service (except during the wars) from 1913 until 1949, or the beloved R.M.S. Mauretania (1907-1935) another four-funneled Cunarder.

Aquitania was even featured on the covers of certain Cunard passenger lists during her early years, even surpassing the French Line’s iconic SS Normandie in such recognition. The Normandie used a style of passenger list identical to other French Line ships, except that her name was across the foot of the page.

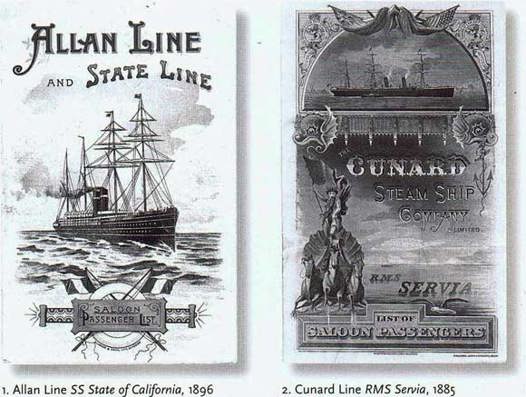

Covers of passenger lists reflected style and design expectations of the day. For example, an 1896 Allan Line booklet looks like it belongs in 1896 (fig.1) and couldn’t be mistaken for a 1920s or 30s.design, and an 1885 Cunard passenger list (fig.2) looks like it belongs in 1885.

Early lists showed the name of each passenger, title, if any, and city or town of residence. By the time of the first meal, the experienced traveller would have reviewed the Passenger List to see whether there were any ‘important’ people on board. If one were in First Class (a.k.a. Saloon, First Saloon, or First Cabin), the quest of the voyage would be to meet celebrities in person and perhaps ask for their autograph. Members of the aristocracy, barons of business, senior clergy, and parliamentarians were all of interest. Beyond that, one would look for other passengers (in the same class) from the traveller’s home community if it were shown on the list.

Equally important for the passenger was remembering the names of the other parties seated at their dinner table. Many passenger lists are annotated with tick marks, underlining, or other symbols as an aide memoire for the names of table-mates. Even more important for some of the elite was the entourage accompanying other travellers in their class. For example, in an R.M.S. Aquitania 1920 passenger list one sees “The Right Hon. The Earl of Craven and Valet” and “The Countess of Craven and Maid”. Numerous other passengers were accompanied by maids or valets. However, some passengers took the competition to a higher level, and the same passenger list shows “Mrs. Leatherbee and three maids.” The likely reaction by the other super-rich would be to bring more of the household staff on the next trip, so that they could trump the entourage of their fellow travellers in the social set. In total there were 20 maids and 6 valets on that voyage. The list also contains “Mr. C. P. Coleman and Secretary”, Master John Raiss and Tutor”, and Master Gallagher and Nurse.” Other lists show chauffeurs, suggesting that the owners’ also brought their own motor vehicles on the ship.

Note that servants didn’t have names. They were merely an anonymous appendage to the names of their masters. This underscores the almost serf-like conditions for staff in many upper class households. Further, servants had small quarters although in close proximity to their masters. Deck plans of the RMS Mauretania of the same era show small quarters on the deck below the First Class suites, with nearby stairways. It wasn’t just maids and servants that were the equivalent of nameless chattels. A pocket-sized 1879 passenger list of Anchor Line’s Devonia shows “Capt. Charles Porter and wife.”

The apex of social competitiveness may well have occurred during a three-day cruise on the RMS Berengaria to observe the Royal Naval Review at Spithead in 1935, to commemorate the King’s 25th Anniversary on the throne. The passenger list shows icons such as Rudyard Kipling and Mrs. Kipling (“and Maid”); Mr. Frederick M. Elgar; Lady Brocklebank; Mrs. Oswald Mosley; the Hon. Mary, Jean, and Sheila Parnell; five members of Canada’s Eaton family, owners of Canada’s largest department store chain; and a phalanx of the nobility and Members of Parliament. If one were to combine this passenger list with those of the R.M.S. Lancastria and the R.M.S. Majestic, the other two passenger ships providing cruises to view the Review, a significant portion of the British upper class of the day would be represented.

It would be interesting research to track the number of maids, valets and other servants on passenger lists of a ship over many years, to trace the reduction in the number of servants and other household staff. The best ships to use would probably be one or both of the R.M.S. Aquitania, a large, prestigious four-stacker in service (except during the wars) from 1913 until 1949, or the beloved R.M.S. Mauretania (1907-1935) another four-funneled Cunarder.

Aquitania was even featured on the covers of certain Cunard passenger lists during her early years, even surpassing the French Line’s iconic SS Normandie in such recognition. The Normandie used a style of passenger list identical to other French Line ships, except that her name was across the foot of the page.

Covers of passenger lists reflected style and design expectations of the day. For example, an 1896 Allan Line booklet looks like it belongs in 1896 (fig.1) and couldn’t be mistaken for a 1920s or 30s.design, and an 1885 Cunard passenger list (fig.2) looks like it belongs in 1885.

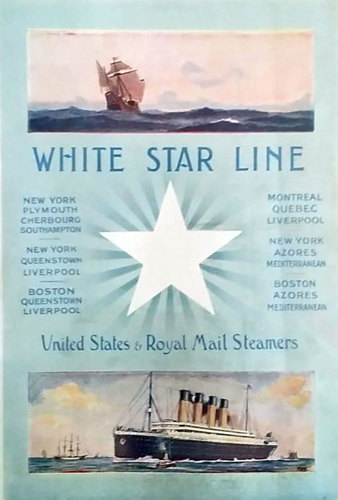

The 1920s and 30s marked the peak of dramatic artwork, particularly on Cunard and Canadian Pacific ships. Others, like White Star Line, lagged behind. For example, the turgid design from a White Star Line list from the Cymric’s voyage of September 9, 1913 was still being used for passenger lists of 1924, eleven years later. Was this lack of innovation a surrogate for the decline and eventual failure of the White Star Line?

Above, the 1913 passenger list cover from White Star Line SS Cymric

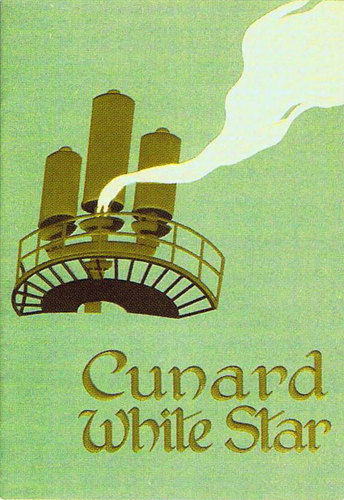

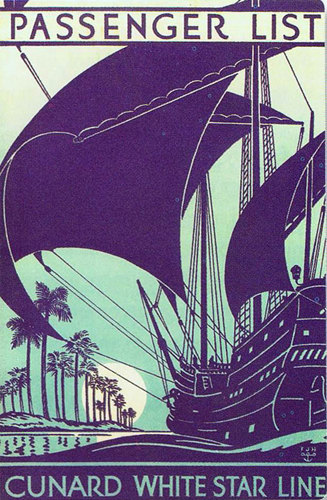

In contrast, Cunard produced a solid array of creative artwork. For the frequent traveler across the North Atlantic, Cunard’s’ approach would have added at least a small touch of variety to each trip - some of the 1920s and 1930s classics have real charm.

Above, the passenger list cover from Cunard White Star Line RMS Samaria, 1935

Above, the passenger list cover from Cunard White Star Line MV Georgic, 1938

Above, a 1927 passenger list cover from Cunard Line RMS Antonia.

After World War II this approach gave way to more prosaic designs such as the cover of a Queen Mary 1947 First Class passenger list:

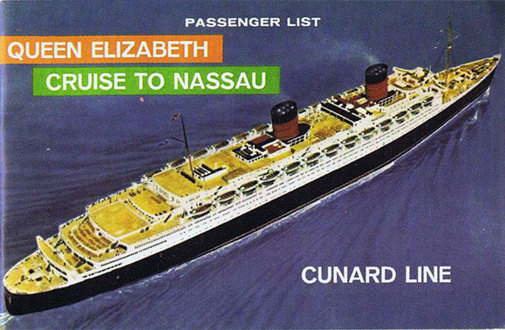

Only a few bright spots such as a 1963 RMS Queen Elizabeth cruise to the Caribbean relieved the monotony.

For private cruises such as a 1956 occasion where the RMS Mauretania was booked for a Caribbean cruise for General Electric employees and customers there could be a riot of colour (this one even has ‘sparkles’ in the design):

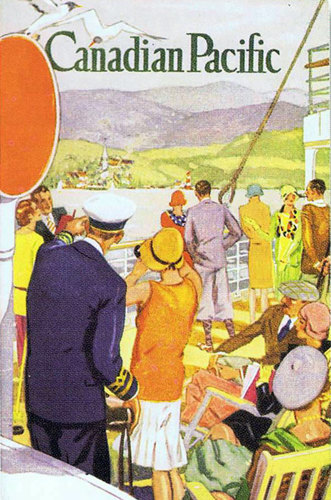

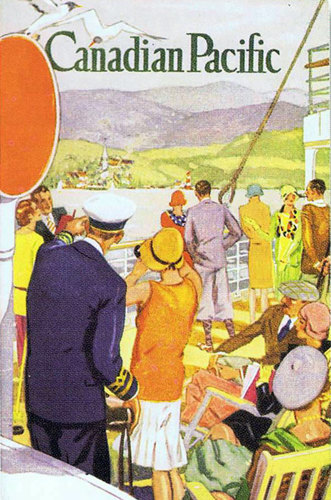

Canadian Pacific produced some of the most artistic covers. Some designs pictured a relaxed lifestyle:

Above, a Canadian Pacific SS Empress of Britain passenger list cover from 1932.

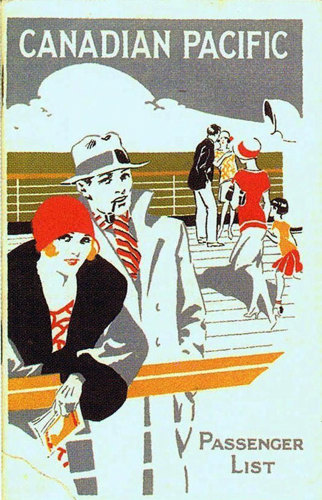

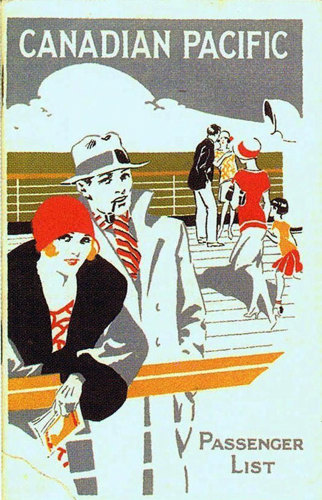

Below, a Canadian Pacific SS Duchess of Richmond passenger list cover from 1929.

Above, a Canadian Pacific SS Empress of Britain passenger list cover from 1932.

Below, a Canadian Pacific SS Duchess of Richmond passenger list cover from 1929.

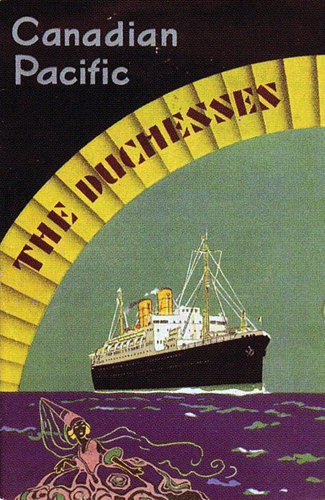

While others promoted a particular class of ship, the Duchesses and the Empresses:

Others were powerful Art Deco expressions:

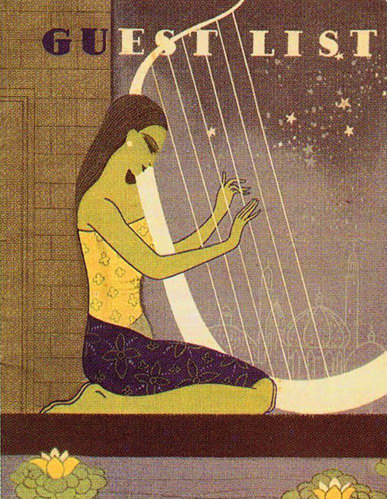

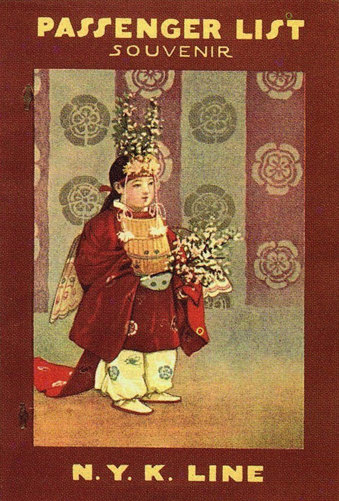

Passenger lists of liners spanning the Pacific ocean could be as artistic as those crossing the Atlantic. Dollar Lines styled their as a ‘Guest List’, while Japan’s NYK labelled theirs as a ‘Souvenir’.

Above, the passenger list cover from Dollar Line SS President Wilson, 1937.

Above, the passenger list cover from Japan's NYK Line SS Siberia Maru, 1929

Other lines merely showed their name and the line's flag:

Unlike the approach taken by dining room menus, the covers were not reflective of special events or seasons, except for the earlier 1927 Cunard cover which carries the Canadian Coat of Arms to recognize the 60th anniversary of Canadian Confederation.

Most writers who love the various facets of their collection could write volumes, and this writer is no exception. There are many other covers, and other aspects, but time and space provide constraints. We collect to capture ‘time and place’, and a slice of social, artistic, design, technological and other history. And even the apparently routine passenger list from an ocean liner has a valuable story to tell.

Text and images ©John G. Sayers

Article first appeared in The Ephemerist in 2007

Reproduced by kind permission of the author

Reproduced by kind permission of the author