This story is an exclusive piece of original research by Paul Louden-Brown FRSA

Paul Louden-Brown FRSA (Fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts) is an authority on the history of the White Star Line.

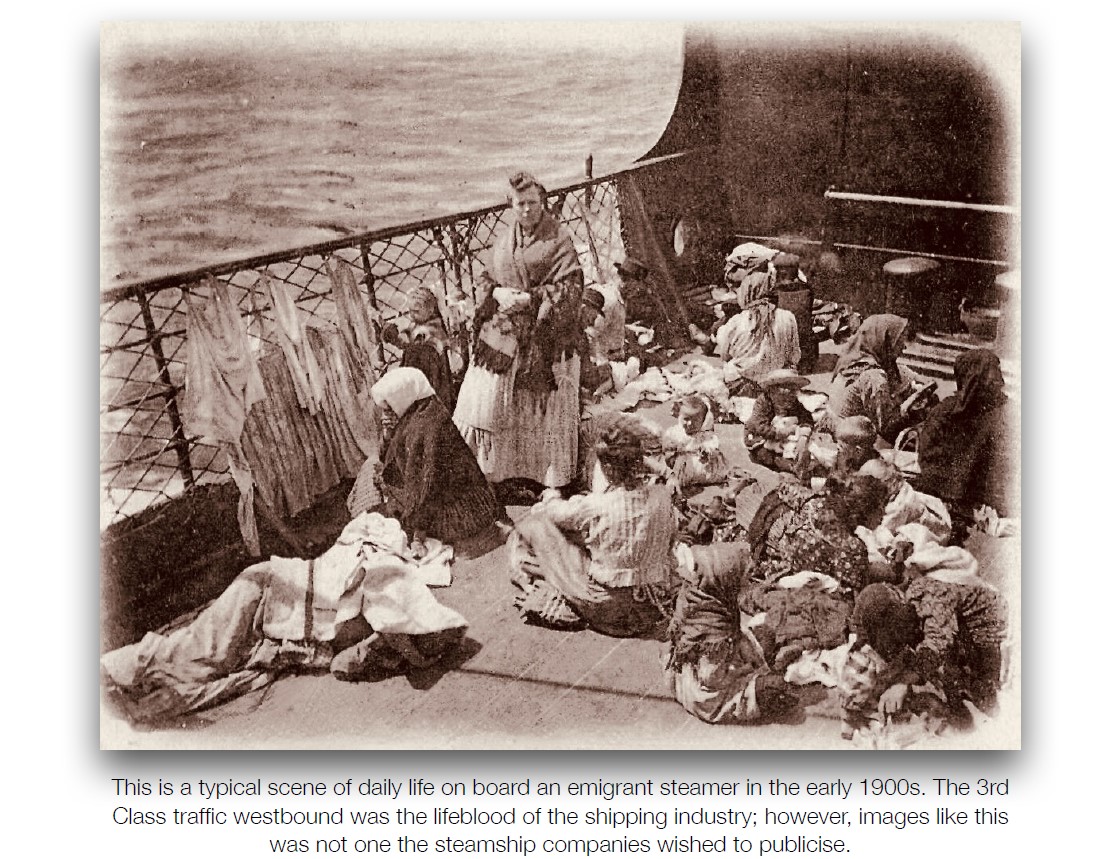

The conversation around immigration today, especially in the United Kingdom, parallels the United States’ attitudes toward the same issues over one hundred years ago. Both countries’ governments also struggled to manage the flow of migrants.

The arguments about the motivations of why migrants made these long journeys by land and sea were almost the same, and distrust of foreigners ‘taking over’ remains sadly all too familiar in some areas of society. And just as it was in Titanic's day, money was at the root cause of migration and the profits to be made, whether legally by shipowners or illegally by people smugglers.

From the moment the flagship of the White Star Line disappeared beneath the waves of the North Atlantic, the world’s print media concentrated almost exclusively upon the fate of Titanic’s 1st Class passengers. Scarcely mention was made of the enormous numbers of emigrants that perished in the disaster.

Many newspapers considered the story of mass migration taboo at the time of the disaster. They focused instead on many of the liner’s wealthiest and most famous passengers. Headlines and pages of stories and photographs delved into every aspect of their lives and the fate of each in the few desperate hours before Titanic sank, quickly satisfying the public demand for information about the tragedy. What is perhaps surprising is that today, 112 years after that tragedy, our appetite for information about Titanic’s 1st Class passengers has hardly diminished.

Consequently, the remarkable story of mass migration across the North Atlantic at the turn of the last century and Titanic’s role in the history of the European diaspora has been largely ignored.

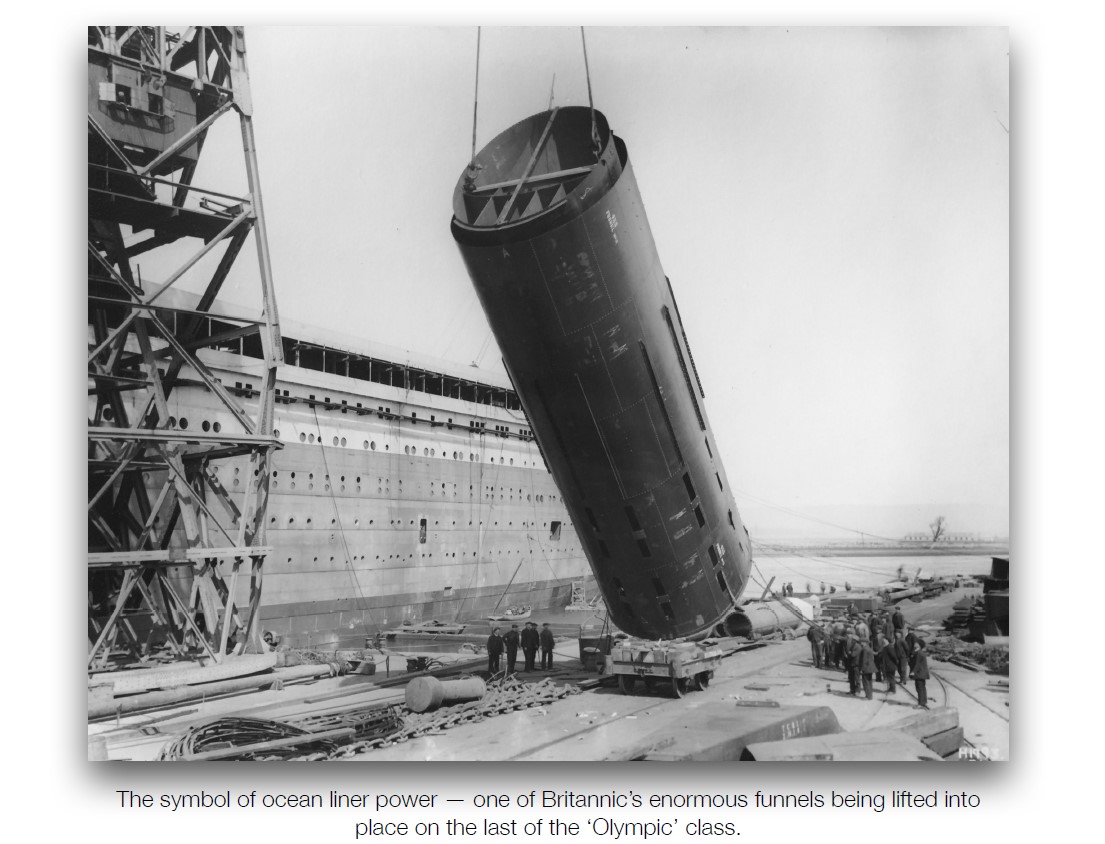

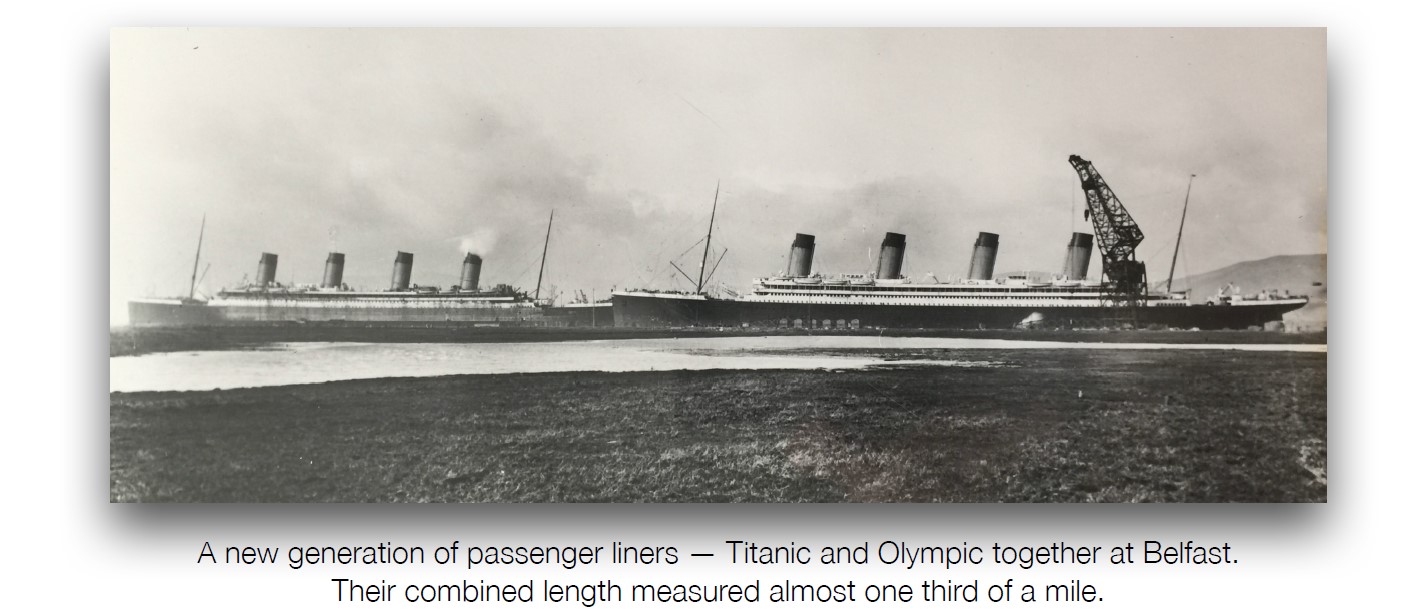

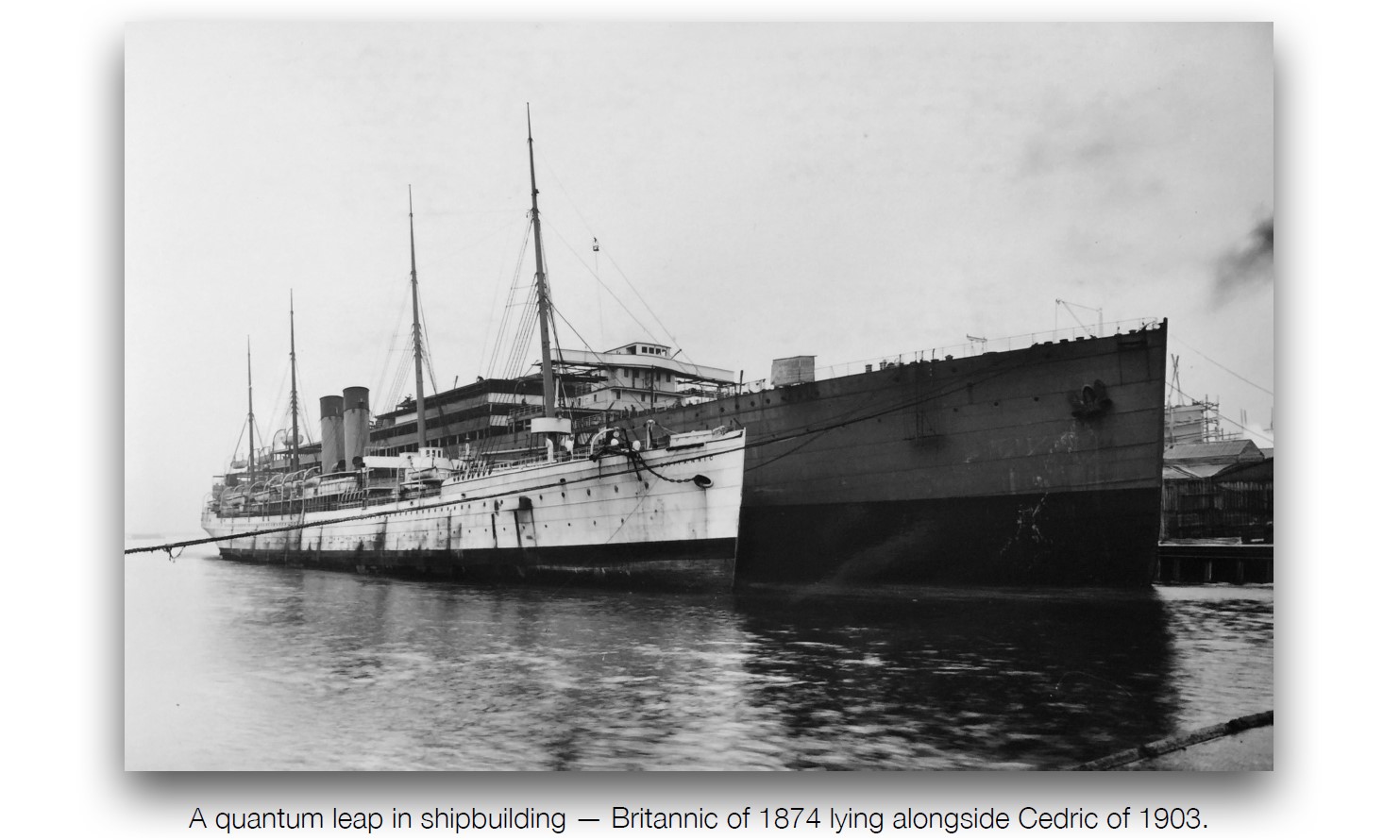

Migration was the most critical factor in the White Star Line's decision to construct Titanic and her older sister ship, Olympic. The giant White Star liners are noteworthy in the history of passenger-carrying steamships, particularly the evolution of the emigrant ship that began in Belfast and ended with the completion of Titanic.

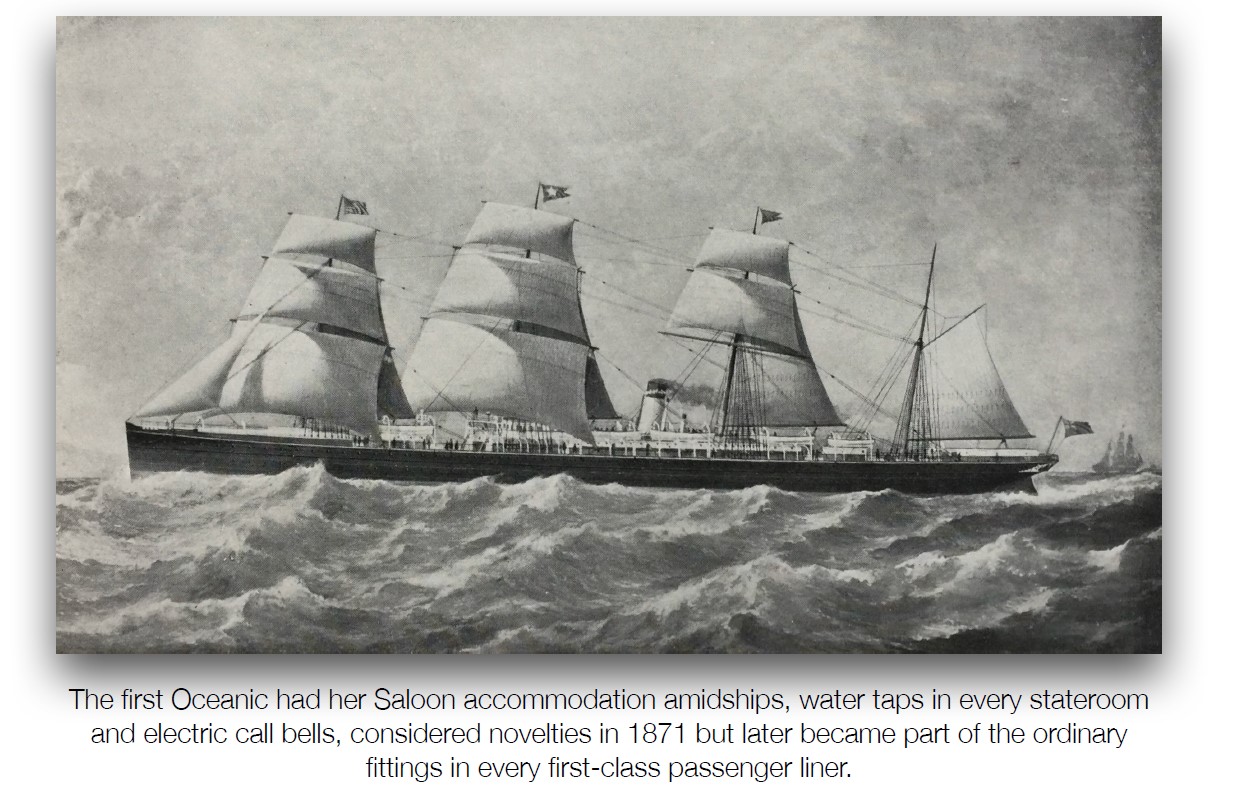

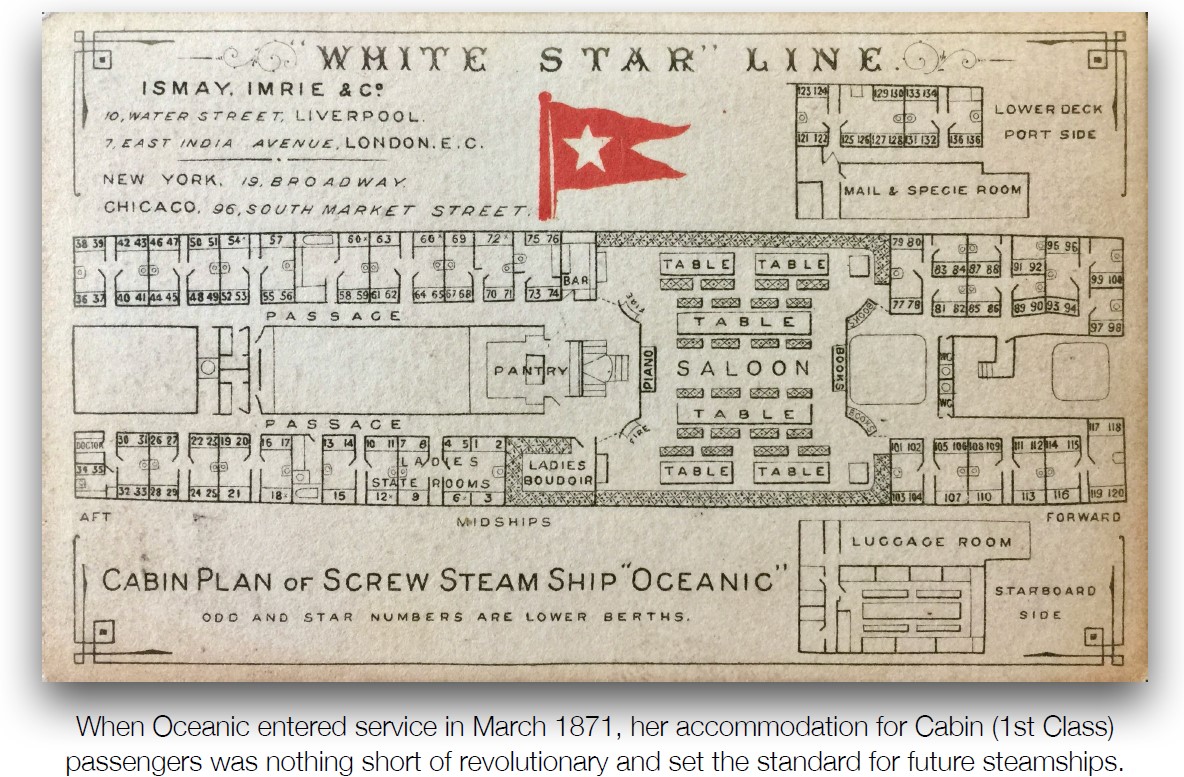

That evolutionary process began in March 1871 when Oceanic, the first steamship built for the newly formed Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, Limited (the official title of the White Star Line), entered the fiercely competitive North Atlantic passenger trade. She was the longest screw steamer afloat at 420 feet; her closest rival was the Inman liner City of Brussels, at 390 feet, then the leading steamship in the American migrant trade; in service, the new White Star liner rendered her rival and every other emigrant ship obsolete.

With Titanic’s launch and entry into service in April 1912, the forty-one-year development of the emigrant steamship reached its zenith. After the disaster that befell the world’s largest liner, the First World War and the virtual collapse of the migrant trade followed. In the 1920s, the US Government imposed further restrictions on the numbers allowed to enter the country and with a stroke of a pen, the days of mass migration across the North Atlantic ended.

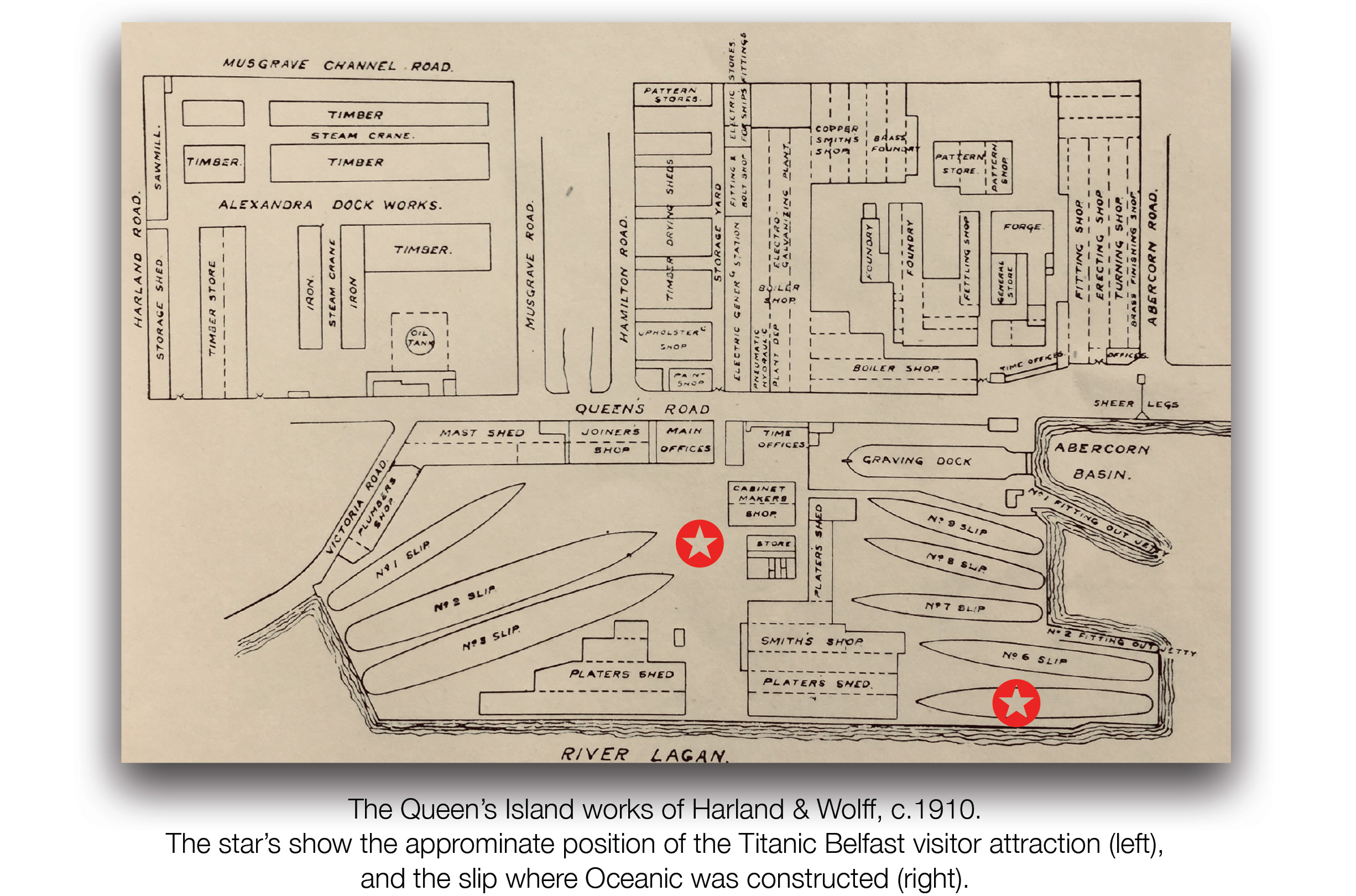

Oceanic, the first White Star steamship, was constructed on No. 1 Slip, a short distance from the main entrance to Titanic Belfast. Each year, thousands of people journey to Belfast to tour the Titanic visitor attraction and other places of interest on Queen’s Island, unaware of the location where one of the world’s most important passenger liners was built and launched.

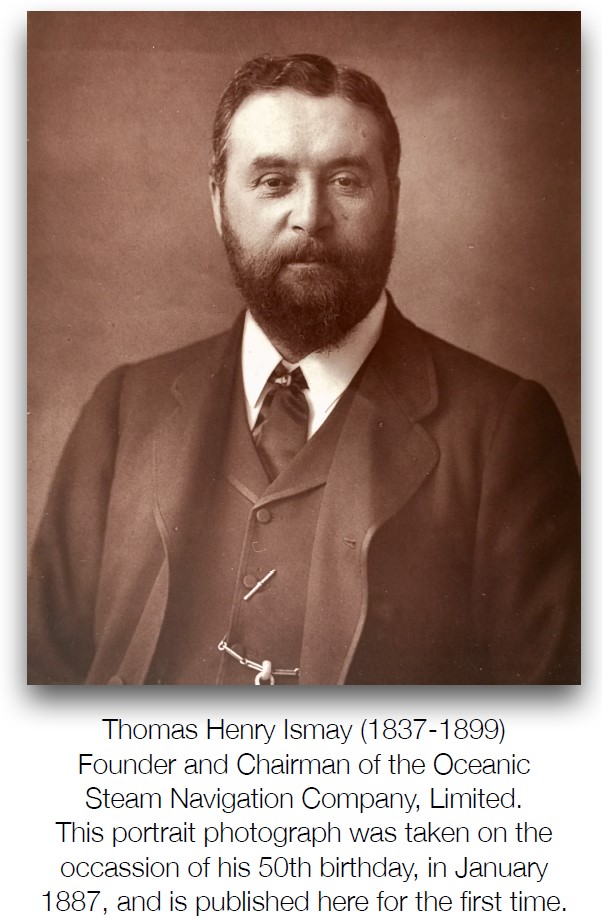

No marker or sign informs us of the vision and foresight of her owner, Thomas H. Ismay, nor the engineering brilliance of her shipbuilder, Edward J. Harland. Titanic overshadows everything.

Oceanic, Yard Number 73, incorporated many innovations in her Cabin passenger accommodation, hull, and machinery spaces. What became known as a ‘ten-beamer,’ her low profile, four-raked pole masts with yards on three and a straight stem gave the White Star liner a graceful and modern appearance. These design features marked a complete break from the traditional clipper bow that many shipbuilders (and owners) carried over from the wooden sailing ships of the past into the modern era of the iron steamship.

One design feature, however, remained familiar. The straight stem first appeared nine years earlier in Castilian and was also designed and built by Harland & Wolff for the shipowners J. Bibby & Sons. This vessel, constructed as a four-master, was 240 feet between perpendiculars, of 663 tons gross. It needed a straight stem due to the limitations of the old Lisbon and Oporto berth, part of Liverpool’s Huskisson Dock system, which was then only 250 feet in length. This change marked a significant departure from the shipbuilding conventions of the time.

The Cabin (1st Class) passenger accommodation had always been placed aft under the quarter deck. According to naval etiquette, this was the place of honour in any ship. However, in rough weather, it was uncomfortable for the highest-paying passengers, and as liners grew progressively in length, the seesaw effect increased. In older steamships, staterooms flanked the Saloon accommodation on port and starboard. This hardly improved matters for these passengers who suffered from the vessel's pitching and poor light and ventilation, as the only means for natural light and fresh air to enter this space was from a skylight. This was fine in good weather, but on the North Atlantic, that hardly ever occurred. Due to the need for skylights, the Saloon had to be placed high in the vessel, causing further discomfort in rough weather. A radical rethink was required.

Left, Thomas Henry Ismay (1837-1899) Founder and Chairman of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, Limited. This portrait photograph was taken on the occasion of his 50th birthday, in January 1887, and is published here for the first time.

Thomas H. Ismay learned from his experience as a director of the National Line that vessels like The Queen, built by Laird Brothers at Birkenhead in 1865, were glorified sailing vessels with a steam engine. Passengers were secondary to the shipbuilder's requirements regarding the placement of engines, boilers and uptakes in a vessel’s most valuable spaces. With the first Oceanic, Ismay decided to discard this outdated concept and situate the Cabin passenger accommodation in the midship section of the ship. By using logic instead of adhering to tradition, internal spaces could be rearranged to provide room for passengers without compromising engine performance. The dining saloon, located forward of the midships, extended across the full breadth of the vessel. The sleeping accommodation for Cabin passengers was in the midship area running aft.

Skylights were still used for light and ventilation over the dining saloon but supplemented by large portholes on the port and starboard sides. The long bench-type tables and seating used in vessels like The Queen were replaced with smaller tables with short seating runs. Two coal-fired fireplaces provided warmth, and a bookcase and piano were used for entertainment. The internal layout in Oceanic satisfied passengers and shipowners and established a highly successful model that every steamship company eventually emulated.

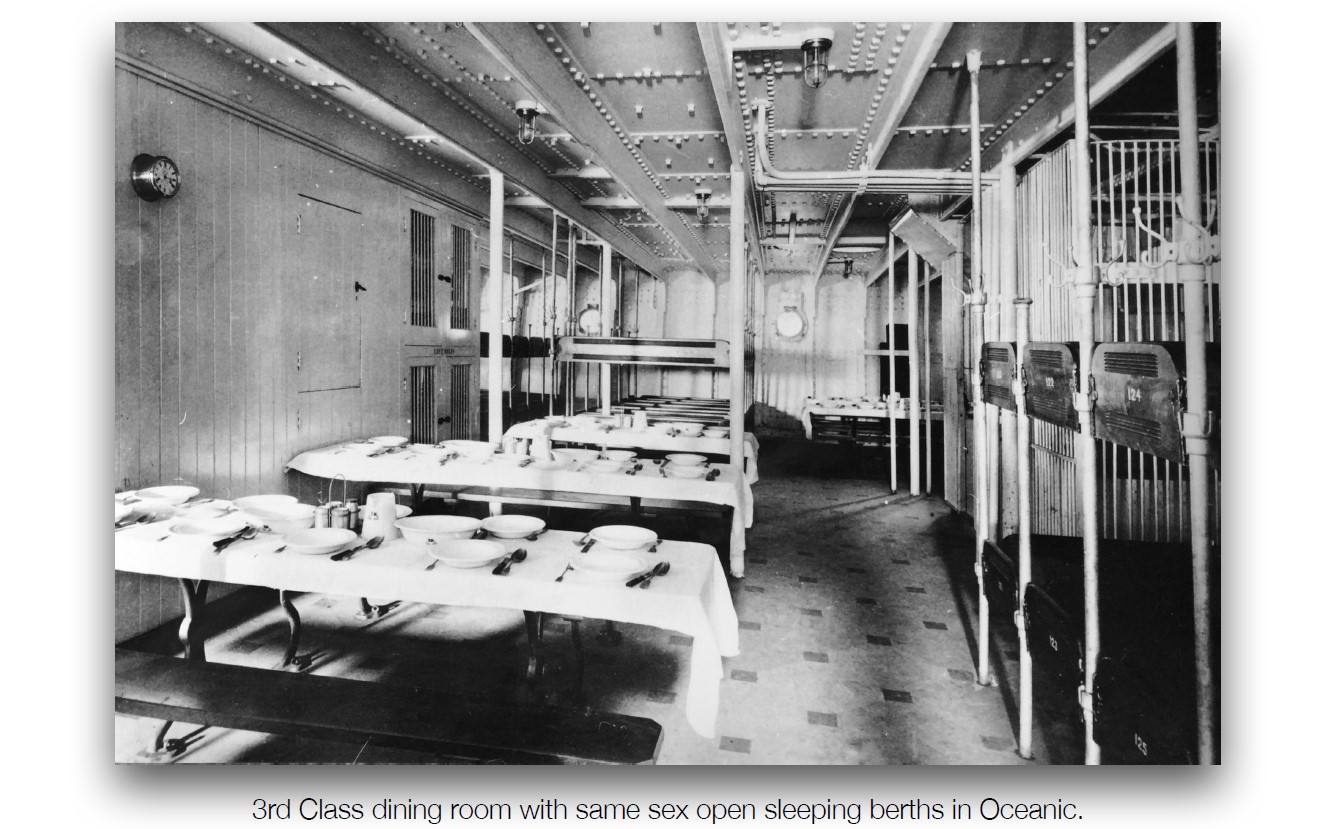

The increasing importance of the westbound migrant traffic led the White Star Line to introduce a series of significant improvements for this class of passengers from January 1894, ahead of its rivals. Before this date, emigrants were required to provide their own outfits for the voyage, including bedding and eating utensils. White Star, from the early 1870s, provided emigrants with bedding, etc., for a fixed price, but it was found that many could not afford even the most basic outfit. The company’s decision to include everything an emigrant would need during the voyage as part of their contract ticket was characteristic of Ismay’s unvarying consideration for the comfort of passengers of whatever class. All emigrants welcomed the new departure because it saved them from carrying an awkward quantity of extra baggage and a considerable reduction in the expense of journeying to the New World; the Liverpool Mercury of 2 February 1894 reported:

‘All the articles provided by the company are of excellent quality, and in particular the plates, mugs, knives, forks, and spoons, from every point of view—strength and appearance—might be used without misgiving by anybody, however fastidious in this respect. Enamelled without and within, and ornamented with the house flag of the White Star Line and an artistic bordering suggestive of, but prettier than, the old willow pattern, the plates to all appearance are composed of china or delft, whilst as a matter of fact they possess all the advantages of the miserable-looking articles usually supplied to emigrants, being unbreakable. The other articles are also stamped with the White Star flag, the bed and blankets supplied being also far superior to the customary articles, and are so made that the outside covers can be taken off and washed after each passage, whilst the actual bed is destroyed.’

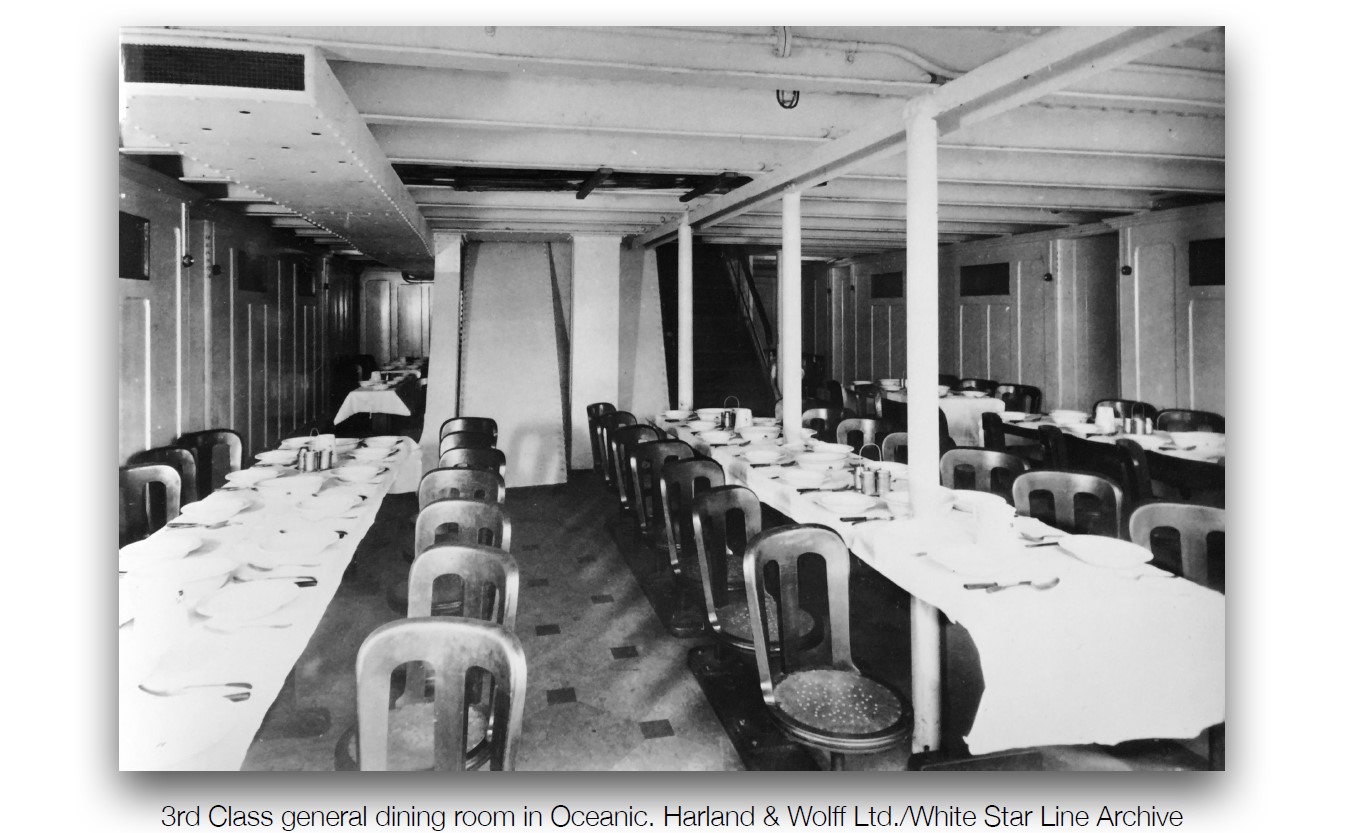

In 1898, four years after the White Star Line inaugurated these changes for emigrants, further improvements were made. Tables in Steerage were laid with tablecloths, and passengers were waited on during meals by uniformed stewards, who washed up and took charge of the eating utensils during the passage. By the turn of the 20th century, White Star had revolutionised travel in Steerage. Even this name, a leftover from sailing ship days, was losing favour and was increasingly replaced by '3rd Class.’

On 6 September 1899, thirty years after the founding of OSNC, Oceanic, the second White Star Line steamship to bear this name and the largest liner in the world, departed on her maiden voyage to New York. When she entered service, speed was paramount in operating large passenger liners. Oceanic maintained a speed of 21 knots and accommodated 410 1st, 300 2nd, and 1,000 3rd Class passengers. Her running mates on the Liverpool to New York service were Teutonic and Majestic, both, by this date, almost ten years old but still capable of an average speed of 20 knots. With these steamers in operation, the concept was born of a three-ship, fortnightly Atlantic service.

In November of the same year, following the death of Thomas H. Ismay, the chairman of White Star, plans to construct a sister ship for Oceanic, to be called Olympic, were first shelved and then abandoned altogether in favour of an entirely new class of passenger and cargo liner. The Board of Trade reserved the name ‘Olympic,’ with the company’s managers renewing the option to use it annually and preventing any other British line from using it.

At the turn of the 20th century, migration patterns fundamentally changed. The North German Lloyd and Hamburg-American lines shared a virtual monopoly of the migrant traffic from central and eastern Europe. Consequently, the number of emigrants from Germany and Russia that reached Liverpool was dramatically reduced. The outlook for White Star’s future share of the 3rd Class traffic westbound from Liverpool looked bleak.

Despite the massive reduction in migrants leaving from the Port of Liverpool, by June 1905, the tremendous westward surge of emigrants exceeded one million for the first time in the history of mass migration. The statistics published by the United States Immigration Service indicated that inward migration to the US for the years ending 30 June 1904 and 30 June 1905 increased by almost 24%, from 812,870 to 1,028,499. Westbound migration was growing, but White Star’s share of the traffic was reducing.

A decade earlier, among the daily sights in Liverpool were thousands of German and Russian migrants waiting to take passage to the United States. Liverpool was always at a geographic disadvantage compared with those ports on the Continent because to reach the Mersey, emigrants had to travel great distances, including long railway journeys on the Continent to a departure port, then by steamer across the English Channel or the North Sea and a further rail journey through England to Liverpool. For many continental migrants, these long and often difficult journeys were expensive, and it was easy to understand why the traffic passed instead to Hamburg, Bremerhaven, Rotterdam and Antwerp, the natural outlets of northern Europe. Because these ports were readily accessible by railway, they attracted large numbers of migrants. Not many years before, the Liverpool steamship companies offered unrivalled facilities; within a few short years, the accommodation provided by the Hamburg-American at Hamburg, the North German Lloyd at Bremerhaven, the Holland-American at Rotterdam and the Red Star at Antwerp was equal to that of their British rivals.

In addition to these improvements for emigrants, the German Government introduced control stations on the German-Russian and German-Austrian frontiers. There were thirteen of these stations located at railway intersections along the borders, each operated by officials belonging to either the Hamburg-American or North German Lloyd, and through these passed a great tide of European migration, which embarked at British, French, Belgian, Dutch and German ports. At the control stations, emigrants were required by German law to submit to a medical inspection; each was deloused and their baggage fumigated. Those not meeting the requirements of that country or who obviously could not comply with the physical test applied to immigrants at US ports were not allowed to pass over German soil. Every year, thousands were turned back to the country whence they came. The German system had its origins in the terrible cholera epidemic of 1892 when the Port of Hamburg was severely affected, the disease presumably being introduced by Russian emigrants bound for the United States. At that time, Hamburg was a major centre of emigration for Russian Jews, and within a matter of months, an estimated 10,000 of the city’s residents and emigrants died.

The control stations were successful in limiting the spread of contagious diseases. However, it was only a short time before the system was corrupted, with the German lines creating a virtual monopoly over northern and eastern European migrant traffic. Instead of passing emigrants through the stations, steamship officials prevented those even with pre-paid contract tickets for foreign steamship companies from passing, forcing, in many cases, emigrants to transfer to one of the German lines or to purchase new tickets from Hamburg-American or North German Lloyd.

If emigrants avoided being detained at any one of the control stations and managed to reach one of Berlin’s main railway stations, agents of the German lines were on the lookout and, with the connivance of the police and railway officials, detained any emigrant not holding a ticket by one of the German companies. These practices were illegal, but there was nothing an emigrant could do but change their ticket or purchase a new one, and if they refused, they faced being sent back to their home country. The reduction in the number of migrants from Germany and Russia reaching Liverpool as a consequence of these practices was dramatic; after many years of enormous numbers leaving Liverpool, migrants still came from Scandinavia (Denmark, Norway and Sweden), Finland, and those parts of Russia via the North Sea and the Baltic, but not in anything approaching the numbers as previously from northern and eastern Europe.

The first steamship company to react to this threat to its share of the migrant traffic was the Cunard Line. The company withdrew from the North Atlantic Passenger Conference and, in December 1903, announced it had entered into an exclusive agreement with the Hungarian Government to embark emigrants from the Mediterranean port of Trieste to the United States. No other steamship company was allowed to share in this traffic. The new service directly challenged the German lines and started a damaging rate war among the North Atlantic steamship companies, which saw fares for Steerage, or 3rd Class as it was increasingly called, falling to as little as £2.

For many years, and long before the formation of the International Mercantile Marine Company, various attempts had been made to secure ‘pooling’ arrangements between the steamship companies. Conferences and pools largely controlled passenger rates. Under the titles ‘Atlantic Conference’ and, latterly, the ‘North Atlantic Passenger Conference,’ the companies sought to agree upon rates for 1st, 2nd and Steerage (3rd Class) passenger and freight rates between Europe, the United States and Canada. Of all these pooling agreements, the one concerning the 3rd Class traffic westbound was the most important.

The terms ‘pool’ or ‘pooling’ in this context referred to a combination of several business concerns for their mutual interest; all partners agreed upon certain principles regarding the distribution of expected profits. In practice, the effect of pools was to prevent competition between its members, establish rates for passenger and freight traffic and thereby prevent competition from newly established shipping lines. At best, these pools of common interest were uneasy alliances. Often, disputes broke out between the various lines. Some of these so-called ‘rate wars’ were disastrous episodes and resulted in significant financial losses for the pool lines. In the case of the action taken by the German members of the Conference after Cunard’s agreement with the Hungarian Government, it was estimated the ‘rate war’ of 1904-05 cost the passenger lines an estimated £1.1m in lost revenues (almost £168m in today’s money), of which £450,000 had been lost by the International Mercantile Marine Company and £300,000 by the Cunard Line.

A settlement was finally reached between the lines, and by January 1905, fares had returned to their pre-rate war levels. However, this costly and protracted fight left the British companies vulnerable to further German expansion into the 3rd Class traffic westbound and, in the case of White Star, with limited options for the future development of their Liverpool business. The company could continue to operate its mail, passenger, and freight services from Liverpool, hoping that conditions might improve. Unfortunately, the already established Scandinavian-American Line and, in June 1913, the newly formed Norwegian America Line threatened their remaining share of the Scandinavian migrant traffic. Instead, it could choose to directly challenge the German lines and transfer some of its newer and faster steamers to Southampton, operate an ‘express’ mail and passenger service from the Hampshire port and embark upon a second building programme, this time with larger tonnage to compete against its German rivals and their plans for new tonnage.

The ‘rate war’ of 1904-05 only accelerated White Star’s plans for the future development of its passenger-carrying business. The company needed to regain its share of the 3rd Class traffic westbound and re-establish its leading position in the Cabin (1st and 2nd Class) traffic. Still, once again, the German lines challenged the British lines’ dominant position in this traffic.

The first direct threat to White Star’s (and Cunard’s) share of the Cabin traffic came from the North German Lloyd when their express steamship Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse entered service in September 1897. The first of four sister ships built with four funnels, she quickly established the company’s reputation as a premier Cabin passenger-carrying line. Her construction heralded a kind of mercantile arms race, with all the major transatlantic companies, including the Union-Castle Line, building four-funnel liners; between 1897 and 1921, fourteen of this type of liner were constructed—eight by the British, five by the Germans and one by the French. The second company to introduce this new type of ‘superliner’ was the Hamburg-American Line, with Deutschland, which entered service in July 1900. These North Atlantic record-breakers could only be operated profitably if they were full. This new class made vessels like Oceanic largely redundant. However, the remarkable speeds of the German liners came at a high price. Higher coal consumption, increased numbers of crew, and, in some cases, serious vibration problems made the operation of these liners both costly and technically challenging.

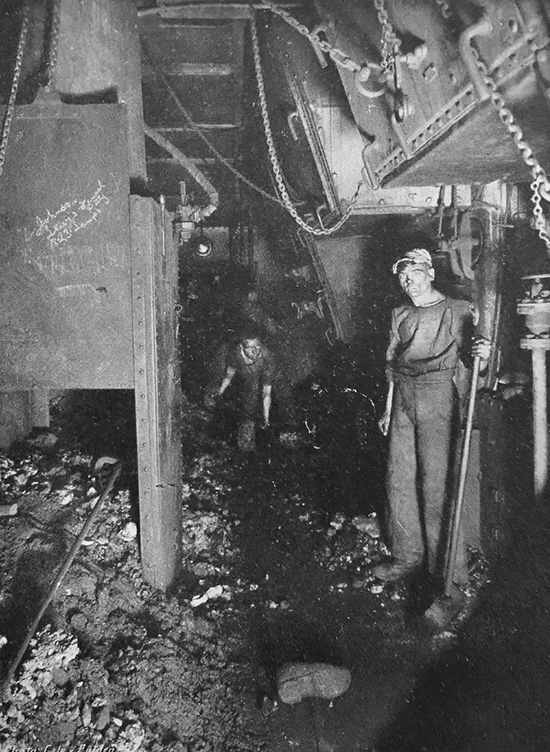

One of the unintended consequences of building larger steamships was their demand for vast quantities of coal to fire the boilers and the need for hundreds of extra firemen, trimmers, and greasers. Known collectively as the ‘black gang,’ these men worked in some of the worst conditions of the modern industrialised age. Only through experience can one understand what the job was like in the age of Titanic. I am fortunate to have had this experience. At age 15 and physically fit from regularly playing rugby and rowing for my school, I volunteered at Exeter Maritime Museum. One of our star exhibits was the ocean-going steam tug and icebreaker St. Canute (built in 1931). She was maintained in steaming condition, and my role was in the stokehold as one of her ‘black gang’ working the boilers and triple-expansion engine. It was exhausting work. First, it required a lot of physical fitness, stamina and endurance to do the job efficiently, including a degree of skill to get the best out of the coal. My duty lasted only a few hours, but in the ‘Olympic’ class, imagine yourself in a close, dust-laden atmosphere with temperatures ranging from 102 to 125 degrees Fahrenheit, undergoing continuous physical exertion for four hours, attending to four furnaces.

Left, In the stoke hold. Like a scene in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, the workers toil in this steel city to keep the boilers fed with hundreds of tons of coal.

There were few opportunities for a momentary break; you pass from one fire to another, shovelling several tons of coal, slicing, pricking up between the furnace bars to detach clinkers, and drawing your slice under the fire to let the draft percolate freely. As you open each furnace door, the heat, accompanied sometimes by flames—if the coal was inferior and the draft bad—rushes out and scorches your face. At the end of your four-hour watch, under these conditions, and having probably concluded your labours by partially drawing and cleaning two or three fires, you will find yourself quite exhausted and will regard the eight-hour interval before your next watch as none too long.

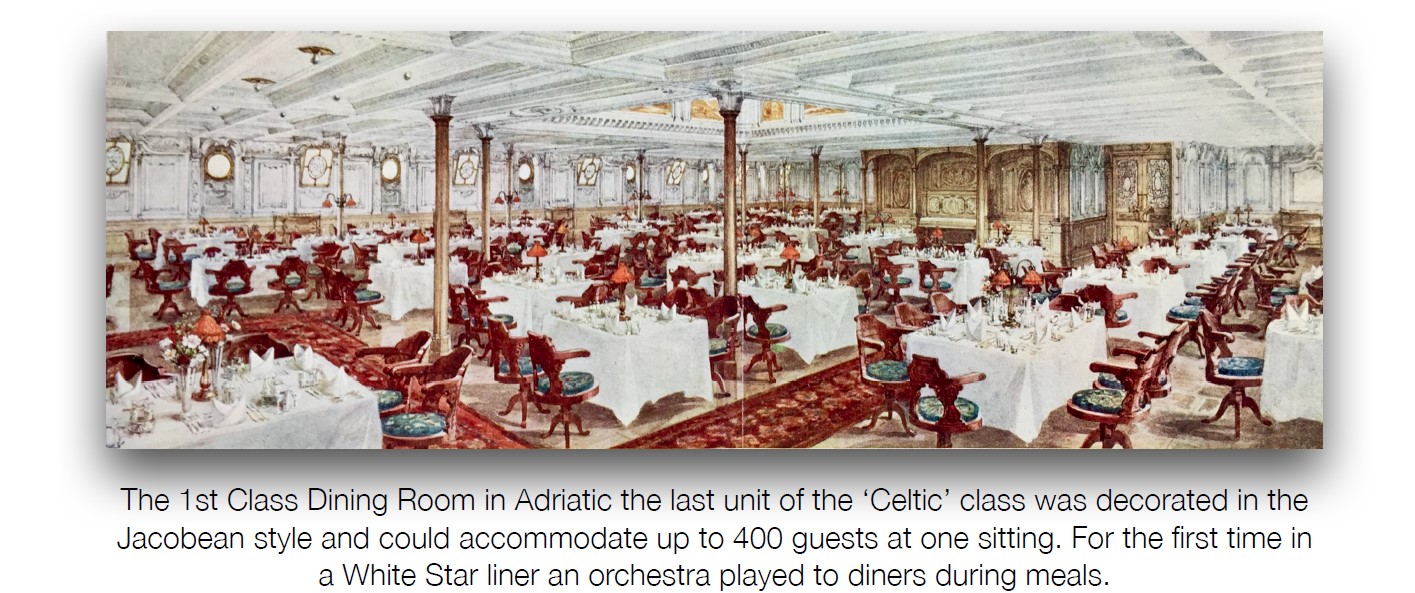

Contrast this dark, labyrinthine world with the life of passengers in 1st Class. Oblivious to the world beneath their feet, the dining saloon in Adriatic was described as ‘perfection afloat.’ Gone were the long bench-style tables and seats, replaced by small tables with swivel seating for two, four, six and eight diners. So many new and revolutionary features were tried in the White Star liner for the first time that she should be considered a prototype of the ‘Olympic’ class.

The only solution that presented itself for the White Star Line to regain its preeminent position in the Cabin and Steerage businesses and counter the growing challenge from Cunard and Hamburg-American’s plans for even larger passenger liners was to build a new giant class of passenger liners.

Concept planning for what eventually became known as the ‘Olympic’ class began as early as 1899. Liverpool was then the most important passenger and cargo port in the British Isles; however, the company’s managers recognised the growing importance of Southampton. Its proximity to London and easy access to the Continent made the Hampshire port attractive to American businessmen and tourists.

The southern port also had significant advantages over its northern rival. A double tide, suited vessels with deeper drafts, and Southampton’s extensive water-frontage would allow for the future development of the port’s infrastructure. A new ‘express’ service to New York via Cherbourg and Queenstown would also help maintain and potentially increase the company’s share of the 3rd Class traffic westbound. On the return leg or eastbound sailings, its steamers, calling at Plymouth before Southampton, would allow the mails and Cabin passengers to be landed and taken by express train to London, making considerable savings in arrival times. The call at Cherbourg, westbound and eastbound, and complimented by a direct rail service between the French port and Paris, would also prove popular with Americans.

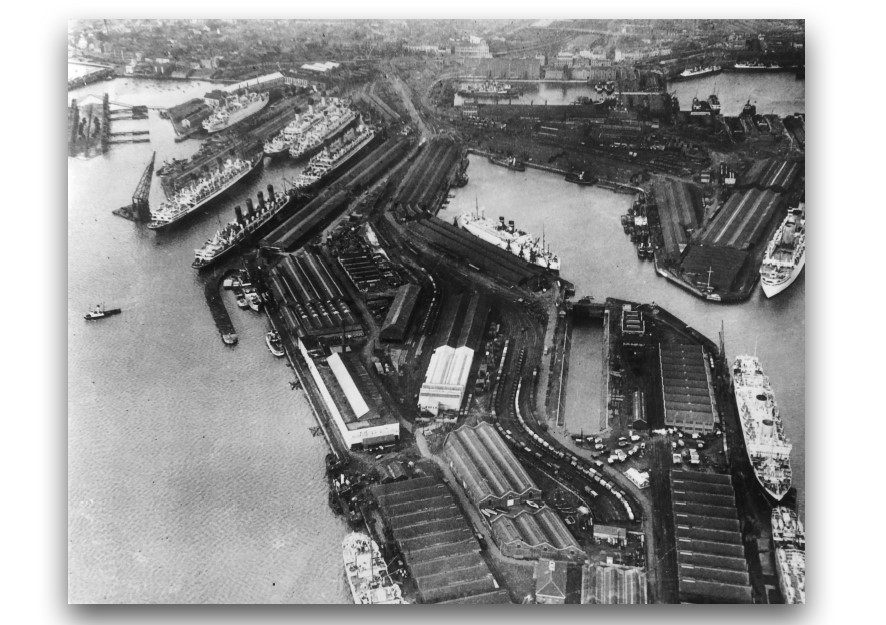

Right, Southampton — Britain’s premier passenger shipping port during the interwar years —photographed from a flying boat.

J. Bruce Ismay, the eldest son of the founder of the White Star Line and the new president of the International Mercantile Marine Company, was a person of vision and foresight. He dedicated his time to studying the challenges of managing and operating large passenger liners. He concluded that for any new class of liners to be profitable, they needed to make an average of 14 voyages per year. Operating at an economical 21 knots and with turnaround times in New York taking at most three days, Ismay believed it would be possible to challenge the passenger-carrying numerical supremacy of the German lines and regain some of the Cabin business lost to the Cunard Line.

To achieve this goal, very little cargo could be accommodated; this would mean a complete departure from the earlier passenger/cargo steamers of the 'Celtic' class. These vessels supplemented passenger earnings by carrying vast quantities of American goods and agricultural produce eastbound and, in the winter months, operating between New York and the Mediterranean for line voyages and pleasure cruises.

Joseph Bruce Ismay (1862-1937) was described by one of White Star’s managers as a ‘handsome autocrat if ever there was one’ and a ‘commanding personality.’

Because of their size and limited bunker space, the ‘Olympic’ class was only designed to operate between Southampton and New York. Initially, White Star had planned to order replacement tonnage for Majestic and Teutonic liners not that dissimilar to Oceanic. However, the idea that the ‘Olympic’ class was the answer to his company’s problems and those of the International Mercantile Marine Company became an idée fixe for Ismay.

The construction of Oceanic took 892 days from keel laying to handover. The ‘Celtic’ class liners took, respectively, 842 days (Celtic), 841 days (Cedric), 748 days (Baltic), and 1,620 days (Adriatic). The extra time taken for the construction of Adriatic, almost 4½ years, may be explained by the vast disruption and massive rebuilding work undertaken at Harland & Wolff’s shipyard in preparation for the laying down of the first unit of the ‘Olympic’ class in December 1908, and the size and complexity of Adriatic’s lavish interiors. The ‘Olympic' class would also have to be constructed without the benefits of low-interest loans or government subsidies. Apart from the annual mail contract, the White Star Line would not receive any financial support from the British Government.

The momentous decision was made, and on 30 April 1907, the shipbuilders Harland & Wolff at Belfast received the order to proceed with the detail design and construction of Yard Numbers 400 and 401 - the world’s largest passenger liners. Despite the new US Immigration Act of 20 February 1907, coming into force on 1 July, and the subsequent doubling of ‘head tax’ from $2 to $4 on every emigrant collected by the steamship companies, the wisdom of the decision to construct the first ‘Olympic’ class liners seemed to be justified when the Trans-Atlantic Passenger Association published the annual results for 1909. As predicted, things had not improved; between 1 January and 31 December of that year, the 3rd Class traffic westbound arriving at US ports from British ports had fallen to 244,647, compared with 433,860 from northern European ports. It was clear to the White Star managers that the numbers leaving from Liverpool were unlikely to recover, and relatively modern vessels like Oceanic (transferred to the company’s new Southampton-New York service in June 1907) were proving challenging to fill and too costly to operate. On Oceanic’s February 1909 westbound sailing, she landed just 257 3rd Class passengers in New York. By comparison, on the same date, the North German Lloyd liner Scharnhorst (built in 1904) landed 1,455 Steerage. It was true all White Star passenger steamers up to and including the introduction of Adriatic, to offset any losses on sailings when passenger numbers were low, were able to carry substantial quantities of American manufactured goods and agricultural produce; however, here again, the European lines held a distinct advantage because the largest market for these goods and produce was on the Continental mainland, entering through Antwerp, Rotterdam, Bremerhaven and Hamburg. White Star (and Cunard) could not hope to compete for the lucrative transatlantic freight business on anything approaching an equal footing with their European rivals without access to one or all of these important seaports.

Above, the Syren & Shipping caricature of J. Pierpont Morgan ‘playing’ with the cream of British shipping.

The great American banker and financier J. Pierpont Morgan is always credited with providing the funds to build the ‘Olympic’ class. This is all the more surprising after the criticism against him following the creation of the International Mercantile Marine Company. The public, particularly in Britain, had been whipped up by a xenophobic press hostile about the sale of the country’s national shipping lines’ to what was portrayed as the ‘Yankee invader’ and the giant monopoly he created, nicknamed the ‘Morgan Combine’ (herein referred to as IMMCO). Despite what was written in the general press and in certain shipping publications from the pens of those who had access to information which should have led them to more accurate conclusions about the prospects for the new Combine, some voices pointed out that no man in competitive trade can make money by giving an excessive sum for businesses, however great, which still left open enough free facilities to afford the public possibilities of using other means of satisfying their requirements. In other words, though it might be worthwhile to pay heavily for a true monopoly, it is not sound business to give more than a thing is worth in a trade that continues to be competitive.

The White Star Line, IMMCO’s principal passenger line, could not hope to challenge the numerical supremacy of the German companies or match the speed of the new Cunard flyers or their government financial backing. The only route open to the managers was to build the world’s largest ships and operate three instead of four in the newly established Southampton-New York mail and passenger service and run these vessels at moderate speeds, matching the kind of reliability in arrival times that the railway companies achieved, and thereby making significant economies through scale. The White Star Line, to fund the construction of the ‘Olympic’ class without government support, would be making a substantial financial gamble. It was a daring plan that had never before been attempted by a leading steamship organisation.

White Star’s business model was primarily based on the assumption that US immigration would continue to increase and that no serious attempt would be made to restrict the flow of migrants westbound for the next twenty-five years, the typical service life of a first-class passenger steamship. However, this assumption was fallacious.

By the early 1900s, it was already widely accepted in international shipping circles that the days of unrestricted immigration into the United States were numbered. Several US Government acts had introduced stricter medical examinations, including heavy financial penalties if steamship companies landed emigrants suffering from any medical or mental conditions. New laws to prevent immigrants from being brought over as contract labour restricted the flow of cheap labour. Immigration had become a heated political issue. US President Theodore Roosevelt voiced his frustration with the way the steamship lines were conducting their business in a message to Congress:

‘The most serious obstacle we have to encounter in the effort to secure a proper regulation of the immigration to these shores arises from the determined opposition of foreign steamship lines, who have no interest whatever in the matter save to increase the returns on their capital by carrying masses of immigrants hither in the steerage quarters of their ships.’

In February 1907, President Roosevelt and Congress formed the United States Immigration Commission (also known as the Dillingham Commission) in response to increasing public and political concerns about the effects of unchecked immigration and its impact on the socioeconomic life of the nation. During its three years in operation, the Commission employed a large staff of researchers and statisticians, spent over $1 million, accumulated a wealth of data, and produced the first comprehensive study on migration; in 1911, its research work was published in a 41-volume survey and made uncomfortable reading for steamship company managers. The Commission concluded that immigration from eastern and southern Europe seriously threatened American society and culture and should be significantly reduced in the future (as well as recommending the continued restrictions on immigration from China, Japan, and Korea).

In light of the imminent threat of legislation restricting the numbers allowed to enter the United States, it is difficult to comprehend why the company constructed the ‘Olympic’ class liners when these vessels were only intended to operate on the transatlantic route between Britain and the United States, unlike the company’s intermediate liners, such as Celtic, Cedric, Baltic, and Adriatic, which were employed on pleasure cruises and line voyages from New York and Boston to the Mediterranean when the number of emigrants travelling across the North Atlantic in the winter and spring seasons was at its lowest. Liners of the size of the ‘Olympic’ class could not be accommodated at many ports in the Mediterranean, severely limiting their earning ability. They were also built with limited bunker space, only sufficient for a round voyage (westbound and eastbound); therefore, coaling these monster vessels would be logistically impossible at many smaller ports.

Dependence on 1st Class traffic, both westbound and eastbound, was more problematic. This passenger class was notoriously fickle and would often change sailings to a newer steamship entering service for the first time. Therefore, it could not be depended upon. And this class of passenger was far from as profitable as the cost of their contract ticket suggested. It was a fact that the emigrant paid only a fraction, not more than a fifth or sixth, of the sum paid by a 1st Class passenger, but then the latter required ten times the attendance. He was, especially if American, and still more especially if she was an American, extremely meticulous, not to say hypercritical, insisting on the luxuries of an up-to-date hotel, an elaborate menu at meals, and ices ad libitum between whiles. Decorations and furnishings of the most intricate kind involved an immense outlay of capital and had to be supplemented by a regiment of stewards, cooks and bottle washers. The result was that the 1st Class passenger was less profitable a person than his humbler brother in 3rd Class. The asparagus out of season served at the table in the dining saloon cost as much as the roast beef plentifully served in the emigrants’ quarters. Hence, no steamship owner or manager in their senses would think of neglecting the 3rd Class traffic or giving their service a bad name to save a few pounds on the commissariat.

By the turn of the century, in 1900, Atlantic passenger traffic had grown to such proportions and importance that 260,000 Cabin (1st and 2nd Class) passengers crossed between New York and European ports every year, created by the enterprise of Liverpool shipowners. Their French and German rivals were, in this respect, mere imitators. The initiator of the modern floating hotels, recognised as palaces of luxury, was the White Star Line chairman, Thomas H. Ismay. His originality and business genius were instrumental in building up the brilliant fortunes of his company through these means, marking a significant milestone in the evolution of the transportation industry.

The White Star service, renowned worldwide, was marked by a unique charm unlike anything in the United States. It possessed a charm irresistibly attractive to wealthy Americans, ranking high in the eyes of ocean-going connoisseurs, both British and foreign. The ships exuded the atmosphere, distinction, and refinement of an elegant mansion, a stark contrast to the hustle and bustle of a caravanserai, making them a symbol of luxury and comfort afloat.

This fact alone explains why J. Pierpont Morgan was anxious to include the White Star Line in his ‘Combine’ and, by preserving the traditions of the service, capture the cream of the 1st Class business. Despite all that was said to the contrary, there was a comfort to be found in travelling by the leading Liverpool lines, which, with all their extravagance of appointments, their foreign rivals had not yet succeeded in emulating at the turn of the 20th century. Morgan also had good reason to favour the White Star Line over its greatest British rival, the Cunard Line. Morgan had arrived at Liverpool on Christmas Eve by Cunard. The ship’s stewards were too preoccupied with getting home for the holidays that Morgan found himself left to organise getting his family’s baggage across Liverpool for the rail journey to London. A number of American ladies were also inconvenienced, and Morgan rallied several carriages and porters to help these ladies, too. He was said to have been exhausted by the experience, but it was not his way to complain to the Cunard managers, and in the early 1890s, he transferred all his business to the White Star Line. His revenge upon the Cunard Line was forming the International Mercantile Marine Company.

Before the formation of IMMCO, J. Pierpont Morgan had dreamed of establishing a virtual monopoly of passenger and freight services across the Atlantic. The purchase of the entire share capital in the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, Limited brought the great American banker and financier another step closer to the realisation of this dream. OSNC owned the White Star fleet, which was mortgage-free, and there was a large balance to the credit of profit and loss. The fleet was practically unencumbered (apart from several vessels jointly owned with Shaw, Savill & Albion & Company), and earnings for the fleet were at an all-time high because of the South African War and the British Government’s desperate need for tonnage at any price to help prosecute the war against the Boers.

The high price that Morgan paid on behalf of his American investors for the entire share capital of OSNC was excessively high. Starting in 1903, these investors received ever greater dividends on their share capital. In a single year (1906), dividends reached £1,713,522. White Star had little or no ready capital to invest in new tonnage, unlike their great rival, Cunard, which in July 1903 had secured a low-interest loan from the British Government to build a pair of giant express steamers on the understanding that they agreed to remain an entirely British-owned concern. After signing the agreement, the Cunard directors were in a bullish mood. At their back, they had access to enormous sums of cash and the de facto backing of a government partner, something unique in British mercantile economic history at that time. On the other hand, White Star’s managers had no choice but to match the competition and borrow money to construct these giant liners.

J. Pierpont Morgan had no intention of paying any more to develop IMMCO other than the funds initially raised to purchase the various share capitals of the constituent companies that made up the Combine. When the time came to construct Olympic and Titanic (and a third sister ship), funding came from the issue of 1.25 million First Mortgage Debentures of £100 each, offered at £97 10s each, and bearing interest at the rate of 4½ per cent. The total cost of both vessels was estimated at £3.6 million, and the addition of this tonnage necessitated the provision of further capital. The Debentures were secured by a first charge over the entire White Star fleet and the new vessels as completed. The third vessel would be financed with further borrowing. Before Morgan purchased the White Star Line, the company was debt-free, with a large cash balance; after its sale, it was saddled with enormous debts for the next twenty-five years.

From the earliest planning stages for the new ‘Olympic’ class, the accommodation provided for 3rd Class passengers was of paramount importance. The European migrant diaspora to the United States from 1899 to 1909 reached a staggering 8,213,034, and based on these statistics alone, the White Star Line made predictions for its future earnings.

This ten-year high comprised the following age groups: those under 14 years—1,013,974; 14 to 44 years—6,786,506; and 45 years and over—412,554. The occupations of these immigrants were broken down into the following categories: professional—80,322; skilled—1,247,674; farm labourers—1,290,295; farmers—84,146; common labourers—2,282,565; servants—890,093; no occupation—2,165,287 and miscellaneous—172,653. The most significant numbers of races or peoples of this 8.2m (calculated above 100,000) were Italian (south)—1,719,260; Hebrew—990,182; Polish—820,716; German—682,995; Scandinavian—534,269; Irish—401,342; English—355,116; Slovak—345,111; Italian (north)—341,888; Magyar—310,049; Croatian and Slovenian—295,981; Greek—177,827; Lithuanian—152,544; Finnish—136,038; Ruthenian—119,468, and Scottish—112,230.

Titanic was, first and foremost, a passenger liner. The requirements of the Merchant Shipping Act of 1894 set out the minimum space each Steerage passenger required. Her accommodation was designed for 1,026 3rd Class passengers and 674 2nd Class passengers, with sections of this latter class used for extra 3rd Class berths when demand justified it. The numbers provided for 3rd Class passengers in Titanic were not dissimilar to those in Oceanic, which entered service over twelve years before, in September 1899. That vessel accommodated 1,000 3rd Class passengers. However, Oceanic, unlike Titanic, had portable demountable 3rd Class rooms, allowing extra freight to be stowed on eastbound sailings; the cargo handling was achieved by derricks mounted on each of her three masts with powerful steam winches on the weather deck.

Freight was never a significant consideration in planning the ‘Olympic’ class. With only two masts and limited cargo space, Olympic and Titanic carried a fraction of the cargo and refrigerated produce compared to Oceanic and the intermediate steamers Celtic, Cedric, Baltic and Adriatic (known collectively as the ‘Big Four’). The idea behind this quartet of vessels was simple: Maximise the number of migrants a ship could carry westbound and carry vast quantities of American goods and agricultural produce eastbound. On arrival in Liverpool, there were extensive facilities for handling mixed shipments and cold storage in the docks to handle the large amounts of American frozen and chilled beef and pork produce.

Between September 1899, when Oceanic entered service, and June 1911, when Olympic, her replacement, entered service, Oceanic completed 142 voyages - a voyage was a westbound and eastbound sailing starting and terminating at the same port. Of these voyages, Oceanic only exceeded 1,000 3rd Class passengers on 27 westbound sailings. The only significant increase in 3rd Class numbers was in 1904 during the rate war. Rather than the expected financial boost from the extra numbers carried, White Star lost money on almost every 3rd Class passenger booking during this period.

Adriatic, the last of the ‘Celtic’ class, entered service in May 1907. Her first sailing was on the Liverpool-New York service. After this, she was transferred to the company’s new Southampton-New York service, the first White Star liner to directly threaten the supremacy of the German lines on the English Channel route to the United States. Her maiden voyage account showed promising results. She carried 365 1st, 355 2nd and 1,802 3rd Class passengers. However, subsequent westbound sailings between 1907 and 1911 produced disappointing results.

Adriatic became a popular steamer with wealthy American travellers, and, from December 1911, she was employed in the company’s New York-Mediterranean service. On her return from Naples in the same month, she carried 519 3rd Class passengers. The pattern was set in the winter season, typically from November to March, when migration from central and eastern Europe was at its lowest level; Adriatic, Celtic and Cedric were operated on the Mediterranean service, with New York as their terminal port.

The Combine’s ambitious plans to virtually monopolise the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Class and freight traffic, supported by a bipartisan agreement with the German, French and Holland-American lines, would have made the North Atlantic Steamship Conference practically redundant. In its place, IMMCO would be free to set any rates it wished for passengers and freight. Its only concern might have come from the US Government and its anti-trust legislation. However, IMMCO could circumvent much of this because the constituent lines that made up the Combine were nominally still foreign, and most of their tonnage was under the British flag. With this plan in place and Morgan’s grip over much of the US railroad network, it would be hard to imagine his companies or combinations failing. However, the future problems the Combine faced began with its creation.

White Star went from a position of strength as Britain’s leading steamship company to a business with massive loans secured on the entire fleet and rapidly escalating dividend payments. Therefore, it was no wonder that J. Bruce Ismay, in January 1912, notified the IMMCO board of his intention to resign from the presidency and chairmanship of both the Combine and White Star in June of the following year. Ismay knew that the future of the passenger shipping business would be very different from the one he inherited from his father in November 1899.

IMMCO had been a tremendous gamble, but Cunard’s refusal to become part of the Combine meant it would never function as initially devised. The ‘Olympic’ class was White Star’s attempt to regain its position as Britain’s leading steamship company, but there was only a narrow margin between success and failure. Intended as a three-ship service and operating without government subsidies, apart from the annual payment for carrying the British and US mails, the ships needed to be filled as there were no large cargoes to offset operating costs. Unlike the ‘Celtic’ class, the Olympic and Titanic only carried a fraction of their freight, and because of their great size, they could not be used as cruise ships in the winter months when migration was at its lowest.

Olympic, the only unit of the ‘Olympic’ class to enter and maintain regular service, began her service life under somewhat adverse circumstances. Before she left Belfast, there was trouble with the runner crew—these were men specially engaged to shift a vessel from one port to another. One hundred and fifty firemen and trimmers had been specially conveyed to Belfast to work Olympic on her passage to Liverpool and Southampton. Dissatisfied with the terms of engagement, the men left the ship in a body. Local men were employed in their stead, but on reaching Southampton, they demanded an increase of 33% in pay rates. This was not conceded. In September 1911, Olympic was seriously damaged following a collision with a Royal Navy cruiser and returned to Belfast for extensive repairs. The work lasted six weeks and cost an estimated £100,000 (£1.68 million in today’s money). She reentered North Atlantic service in November of that year. In February 1912, she lost a blade from her port propellor and once again returned to Belfast for a replacement. The work was completed in eight days. More delays to her sailing schedule followed after the loss of Titanic when her stokehold crew refused to sail over safety concerns. Three weeks later, Olympic returned to service. In July, leaving New York, her steering gear failed, and the liner ran onto a mudbank. In August, she dropped another blade, this time from her starboard propellor, and returned to Belfast. A replacement was fitted in record time, a remarkable feat, returning to service just one day behind schedule. In September, she dropped a third blade again from her port propellor. The company announced that she would make the next voyage at reduced speed, deciding to postpone fitting a replacement blade until she returned to Belfast for rebuilding. In October, work began building a complete inner skin, part of a programme of safety improvements costing in the region of £250,000 (£4.2 million). The opportunity was taken to enlarge the 1st Class restaurant and make several improvements to her interiors. The work took over five months and was finally completed in March 1913. In July of the same year, she was overhauled at Southampton in the newly extended Trafalgar Graving Dock. Her propellor sets were checked, and sections of the passenger accommodation were further improved; three weeks later, she rejoined North Atlantic service. In December, she underwent a winter overhaul and made the first sailing of 1914 on 21 January.

Despite these disruptions to her sailing schedules, from her delivery voyage in May 1911 until August 1914 and the beginning of the First World War when the regular transatlantic service was disrupted, Olympic made 38 round voyages between Southampton and New York. The White Star Line achieved this only by reducing the turnaround times in New York from an average of six days to three. Considering the long periods she was out of service, this was nevertheless an impressive record.

Less impressive were the estimated 24,500 3rd Class passengers carried on her 38 westbound sailings during this period, an average of only 645 per sailing. Olympic’s 3rd Class was designed to accommodate 1,026. If Olympic had carried numbers in 3rd Class close to her capacity, almost 39,000 could have been accommodated. Sections of 2nd Class could be used for extra 3rd Class berths when demand justified it; however, this was the case only on six westbound sailings. The failure of Olympic to make any significant impression on the 3rd Class traffic westbound and the low numbers carried in 1st and 2nd Classes meant the ‘Olympic’ class would never pay their way.

After the loss of Titanic, the ‘Olympic’ class was seen to have been a terrible mistake, hastening the company’s eventual collapse. One question remains unanswered: the company’s decision to construct the ‘Olympic’ class when the ‘Celtic’ class operated as both liners and cruise ships proved that this model was a reliable money earner and a sound financial investment. Was it vanity that led Ismay to order the ‘Olympic’ class? He had lived in the shadow of his late father and needed to make a name for himself. His relationship with William J. Pirrie, the chairman of Harland & Wolff, was very different from the one between his late father and Sir Edward Harland. Thomas H. Ismay had risen from humble beginnings to become one of Britain’s wealthiest shipowners and the head of one of the world’s greatest shipping lines. However, Ismay senior was a cautious businessman. Pirrie encouraged his son to order ever greater ships, regardless of the economic justification for such enormous and expensive ships. The ‘Olympic’ class should have been the crowning achievement of his son’s career. Instead, its failure marked a significant downturn in the company's fortunes and the cutting short of a promising career.

White Star’s part in the Combine’s plans was crucial to its success. Growing competition for the 1st Class traffic, a shrinking share of the 3rd Class traffic, higher operating costs, massive repair and rebuilding costs, increased wharf and dock charges, rising interest payments and shareholder Dividends, and, worst of all, looming legislation restricting the number of emigrants allowed to enter the United States were problems that could not be overcome even with the building of the ‘Olympic’ class. Just as mass migration was instrumental in the creation of Titanic and her sister ships, it also marked the end of a remarkable era in the history and development of the emigrant ship.

One fact remains: even before Titanic was launched, her fate and the fate of the International Mercantile Marine Company were already sealed.

© Paul Louden-Brown 2024